By Bill Plotkin

Stand still. The trees ahead and bushes beside you Are not lost. Wherever you are is called Here,

And you must treat it as a powerful stranger, Must ask permission to know it and be known. The forest breathes. Listen. It answers,

I have made this place around you.

If you leave it, you may come back again, saying Here. No two trees are the same to Raven.

No two branches are the same to Wren.

If what a tree or a bush does is lost on you,

You are surely lost. Stand Still. The forest knows Where you are. You must let it find you.

—“Lost” by David Wagoner

Over the past two hundred years, industrial civilization has been relentlessly undermining Earth’s chemistry, water cycles, atmosphere, soils, oceans, and thermal balance. Plainly said, we have been shutting down the major life systems of our planet. Compounding the ecological crisis are decaying economies, ethnic and class conflict, and worldwide warfare. Entwined with, and perhaps underlying, these devastations are epidemic failures in individual human development.

True adulthood, or psychological maturity, has become an uncommon achievement in Western and Westernized societies, and genuine elderhood nearly nonexistent.

Interwoven with arrested personal development, and perhaps inseparable from it, our everyday lives have drifted vast distances from our species’ original intimacy with the natural world and from our own uniquely individual natures, our souls. . . .

My beginning premise is that a more mature human society requires more mature human individuals . . . My second premise is that nature (including our own deeper nature, soul) has always provided and still provides the best template for human maturation . . . A third premise is that every human being has a unique and mystical relationship to the wild world and that the conscious discovery and cultivation of that relationship is at the core of true adulthood. In contemporary society, we think of maturity simply in terms of hard work and practical responsibilities. I believe, in contrast, that true adulthood is rooted in transpersonal experience — in a mystic affiliation with nature, experienced as a sacred calling — that is then embodied in soul-infused work and mature responsibilities. This mystical affiliation is the very core of maturity, and it is precisely what mainstream Western society has overlooked — or actively suppressed and expelled.

Although perhaps perceived by some as radical, this third premise is not the least bit original. Western civilization has buried most traces of the mystical roots of maturity, yet this knowledge has been at the heart of every indigenous tradition known to us, past and present, including those from which our own societies have emerged. Our way into the future requires new cultural forms more than older ones, but there is at least one thread of the human story that I’m confident will continue, and this is the numinous or visionary calling at the core of the mature human heart.1. . .

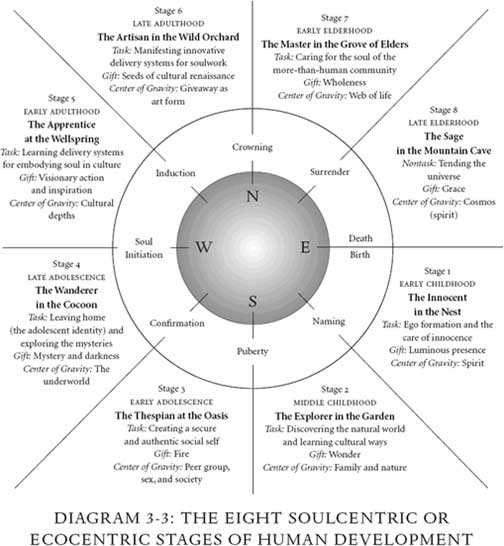

The Wheel of Life

The Wheel of Life is a model of human development that is both ecocentric and soulcentric — that is, a nature-based model that fully honors the deeply imaginative potentials of the human psyche . . . This eight-stage model shows us how we can take root in a childhood of innocence and wonder; sprout into an adolescence of creative fire and mystery-probing adventures; blossom into an authentic adulthood of cultural artistry and visionary leadership; and finally ripen into a seed-scattering elderhood of wisdom, grace, and the holistic tending of what cultural ecologist David Abram calls the more- than-human world.

The Wheel of Life is ecocentric in two respects. First, the eight life stages are arrayed around a nature-based circle (as opposed to the familiar Western linear timeline).

Beginning and ending in the east and proceeding clockwise (which is sunwise), the stages and their attributes are based primarily on the qualities of nature found in the four seasons (east-spring, south-summer, and so on) or, alternatively, the four times of day (sunrise, midday, sunset, and midnight).

Second, the developmental task that characterizes each stage has a nature-oriented dimension as well as a more familiar (to Westerners) culture-oriented dimension. Healthy human development requires a constant balancing of the influences and demands of both nature and culture. For example, in middle childhood, the nature task is learning the enchantment of the natural world through experiential outdoor immersion, while the culture task is learning the social practices, values, knowledge, history, mythology, and cosmology of our family and culture.

In industrial growth society, however, we have for centuries minimized, suppressed, or entirely ignored the nature task in the first three stages of human development, infancy through early adolescence. This results in an adolescence so out of sync with nature that most people never mature further.

Arrested personal growth serves industrial “growth.” By suppressing the nature dimension of human development (through educational systems, social values, advertising, nature-eclipsing vocations and pastimes, city and suburb design, denatured medical and psychological practices, and other means), industrial growth society engenders an immature citizenry unable to imagine a life beyond consumerism and soul- suppressing jobs.

This neglect of our human nature constitutes an even greater impediment to personal maturation than our modern loss of effective rites of passage, and it has led to the tragedy we face today: Most humans are alienated from their vital individuality — their souls — and humanity as a whole is largely alienated from the natural world that evolved us and sustains us. Soul has been demoted to a new-age spiritual fantasy or a missionary’s booty, and nature has been treated, at best, as a postcard or a vacation backdrop or, more commonly, as a hardware store or refuse heap. Too many of us lack intimacy with the natural world and with our souls, and consequently we are doing untold damage to both….

Joanna Macy and Molly Young Brown explain that the Great Turning is happening simultaneously in three areas or dimensions that are mutually reinforcing and equally necessary. They identify these as

- “holding actions” to slow the damage to Earth and its beings;

- analysis of structural causes and the creation of alternative institutions; and

- a fundamental shift in worldview and values

The primary focus of my work is on the third dimension of the Great Turning, which Joanna and Molly deem “the most basic.” They note that, in order to take root and survive, the alternative institutions created as part of the second dimension must be sourced in a worldview profoundly different from the one that created the industrial growth society. They see such a shift in human consciousness emerging in the grief that so many of us are feeling for a plundered world; in our new understandings from ecology, physics, ecopsychology, and other fields about what it means to be human on an animate planet; and in our deepening embrace of the mystical traditions of both indigenous and Western peoples.

The Wheel of Life provides a means to support and quicken this foundational shift in worldview and values; it offers a set of guidelines for actualizing our greater human potential . . . But I do not mean something implausible or fanciful. I mean what simply amounts to growing up. Rather than become something other-than-human or superhuman, we are summoned to become fully human. We must mature into people who are, first and foremost, citizens of Earth and residents of the universe, and our identity and core values must be recast accordingly. This kind of maturation entails a quantum leap beyond the stage of development in which the majority of people live today. And yet we must begin now to engender the future human.

Consequently, the question of individual human development becomes critical. How can we grow whole so that an ecocentric identity becomes the rule rather than the exception? How can we foster a global ecological citizenry? . . .

The human life cycle is best understood as a story. The Wheel tells a story, in eight acts, of becoming fully human, and it offers a map for reaching that destination. It is at once a model of how human development would unfold in a modern, soulcentric, life-sustaining society — a hypothetical one — and of how it can and does unfold now in our existing egocentric society when there is sufficient support from soul-centered parents, teachers, extended family networks, schools, religious organizations, and social programs.

The Wheel is ecocentric in that it models individual human development from the perspective of nature’s cycles, rhythms, and patterns . . . The Wheel is also soulcentric, in two ways. First, it shows how soul attempts to guide our individual development. Second, it envisions the principal goal of maturation to be the conscious discovery and embodiment of our souls. It can equally well be called the Soulcentric Developmental Wheel.

Given that the human soul is the very core of our human nature, we might note that, when we are guided by soul, we are guided by nature. Both soul and greater nature do guide us in our individual development, whether or not we ask for this guidance. But if we know how to listen, we can benefit much more. Living in an adolescent culture does not banish us from soulcentric development. The assistance of nature and soul is always and everywhere available. In our own society, a large minority of people develop soulcentrically despite the cultural obstacles. The soul faithfully comes to our aid through dreams, deep emotion, love, the quiet voice of guidance, synchronicities, revelations, hunches, and visions, and at times through illness, nightmares, and terrors.

Nature, too, supports our personal blossoming (if we have any quiet exposure to her) through her spontaneities, through her beauty, power, and mirroring, through her dazzling variety of species and habitats, and by way of the wind, Moon, Sun, stars, and galaxies.

The eight developmental stages together constitute a single story, the story of a deeply fulfilling but nevertheless entirely human life. The story the Wheel tells is very different from the one that most contemporary people live . . .

The Power of Here

Wisdom traditions worldwide say there’s no greater blessing than to live the life of your soul, the source of your deepest personal fulfillment and of your greatest service to others. It’s what you were born for. It’s the locus of authentic personal power — not power over people and things, but rather the power of partnership with others, the power to cocreate life and to cooperate with an evolving universe.

Before you find your ultimate place, you are, in a sense, lost. You have a particular destiny but don’t know what it is. It’s like being lost in a forest, as in poet David Wagoner’s image at the opening of this chapter.

You can begin or deepen your relationship to soul in the same way the poet advises you to commune with the forest. None of the nonhumans in the forest — or the world, more generally — are lost. Each one is precisely in its true place, and each one knows every place in the forest as a unique place. They are doing something you do not yet know how to do. You could apprentice yourself to them. The forest, the world, knows where you are and who you are. You must let it find you.

If you don’t yet have conscious knowledge of your soul, you haven’t yet learned the power of place — or the power of Here. To acquire this power, which is the goal in the first half of the Wheel of Life, you must first get to know more thoroughly the place in life you already inhabit. This place consists of your relationships and roles in both society and nature. This is the place in which you are lost, in which you find yourself to be, and from which you can, eventually, find your self. You must treat this place you’re in as a “powerful stranger,” as Wagoner suggests, and educate yourself more fully about what it is to inhabit any place. To inhabit a particular place is to have the potential to do and observe the specific things that one can do and observe in that place. This knowledge about inhabiting a place will help you shift to other places in life (which is done by changing your relationships and roles) and to get to know what it’s like to inhabit those places. You’ll discover that some places feel more like your true place, closer to your ultimate place. By developing your sensitivity about place in this way, you can gradually move to your ultimate place. . . .

Your soul is your true home. In the moment you finally arrive in this psycho-ecological niche, you feel fully available and present to the world, unlost. This particular place is profoundly familiar to you, more so than any geographical location or any mere dwelling has ever been or could be. You know immediately that this is the source, the marrow, of your true belonging. This is the identity no one could ever take from you. Inhabiting this place does not depend on having anyone else’s permission or approval or presence. It does not require having a particular job — or any at all. You can be neither hired for it nor fired from it. Acting from this place aligns you with your surest personal powers (your soul powers), your powers of nurturing, transforming, creating; your powers of presence and wonder.

The first time you consciously inhabit your ultimate place and act from your soul is the first time you can say, “Here” and really know what it means. You’ve arrived, at last, at your own center. As long as you stay Here, everywhere you go, geographically or socially, feels like home. Every place becomes Here.

This is the power of place, the power of Here. Before soul initiation, wherever you go, there you are. After soul initiation, wherever you go, Here you are.

* * * * *

—Excerpted and adapted from Nature and the Human Soul by Bill Plotkin (New World Library, 2008)

BILL PLOTKIN, PhD, is the founder of the Animas Valley Institute and also the author of Soulcraft: Crossing into the Mysteries of Nature and Psyche. Visit him online at www.natureandthehumansoul.com.